By Peter Gajdics

In the spring of 2004, when I was 39 years old, I started writing a memoir about my six years in a form of “conversion therapy” at the hands of a licensed psychiatrist, and the medical malpractice suit I’d filed against the doctor for treating my homosexuality as a disease. Early each morning before my full-time job as a civil servant, and late every night before falling into bed in my high-rise apartment overlooking the Pacific Ocean in downtown Vancouver, British Columbia, I wrote. The entire process—writing about the therapy, as well as relevant events from my childhood—was, for me, less a literary endeavor than it was an act of survival: writing as a means of defiance against the silencing effects of shame. Making meaning out of what had happened to me in the “therapy” drove the writing. The intrinsic support system built into our culture for making meaning out of having cancer, or losing a parent, or even, for that matter, surviving a natural disaster like an earthquake, did not seem to translate for what had happened with my former psychiatrist. In 2004, “conversion therapy” was still hardly even recognized by society as being anything that happened to people, let alone was openly discussed. Without some kind of public validation—from my family, or the culture at-large—for having gone through a potentially catastrophic life event, I had trouble even finding the words to describe my own experiences. Except to write down everything that I remembered. I wrote to make real what at times still seemed unreal.

Though I didn’t realize it early on, writing what I “remembered” essentially meant writing about memory—and not only my own. Some twenty years earlier, shortly before the “therapy,” my mother had “confessed” to me in private, after I had told her that I was gay, that she had been raped in one of the concentration camps where she’d been imprisoned in the former Yugoslavia, post World War II, after which she swore me to secrecy. As I traveled backward in my mind, and on the page, it soon became clear to me that I could not write about the therapy, and also my own childhood sexual abuse, without also writing about my mother’s experiences in the camp, as well as her confession to me; I could not write about my palpable grief and sense of abandonment throughout my childhood without also writing about my father’s childhood as an orphan in war-torn Hungary. My father’s estrangement had become my own, later in life; I had experienced a type of incarceration, not unlike my mother’s in the camp, within my own corporeal self. There was a trajectory to our life stories—from my mother’s rape and my father’s isolation, to my own childhood sexual abuse and later rejection by, and alienation from, my birth family—that carried on from one generation to the next. As a child of trauma survivors, writing about my own shame and fear of annihilation, oppression, meant writing about theirs. Moreover, outside of the context of my parents’ lives, I knew my book would not make sense; it would not tell the “full” story.

Writing about my life was one thing, but writing about my parents’ lives soon became something else entirely. What right did I have to write about them, to include facts about their “former lives” in Europe? I looked to experts, but found little in the way of an ethical compass about memoir writing, particularly as it intersected the kind of shame that tended to live on in survivors of childhood sexual abuse and generational trauma, and the need to speak aloud what were often well-guarded familial secrets. How could I write the truth of my life without also touching on my parents’ lives, the intersection of their histories of trauma with my own?

The few books I did find helped guide me through the sticky, often complicated maze of truth telling. For instance, in The Secret Life of Families: Truth-Telling, Privacy, and Reconciliation in a Tell-All Society, author Evan Imber-Black, Ph.D., helped me distinguish secrecy from privacy when she wrote, “Toxic and dangerous secrets most often make us feel shame, while truly private matters do not. Hiding and concealment are central to secret-keeping, but not to privacy.” There was no revenge to my act of writing. I simply wanted to write the truth, maybe even to discover the truth through the act of writing. Finally, I read Judith Herman’s Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, in which she stated, “Remembering and telling the truth about terrible events are prerequisites both for the restoration of the social order and for the healing of individual victims.” Writing, for me, brought an order of truth to the chaos of lies and deceit.

During this time, I had also begun visiting my parents at the family home, the home of my childhood, for Sunday brunches. After years of estrangement over my sexuality, particularly throughout the six years of “therapy,” our time together settled my heart. What I believed—the fact that their religious convictions as staunch Roman Catholics had prevented them from ever really accepting my homosexuality—held less importance than my own love for them. I would not change, and neither would they.

Following one of these brunches, when I was alone with my mother in the kitchen, I gently broached the subject of my writing and asked if I could include aspects of her life from the camp in a book that I was writing about the “therapy” and the lawsuit—subjects we had always stayed clear of discussing.

“Why would you want to do that?” She turned to face me from the sink.

“I’m your son. Your life has affected me. Is that okay?”

She turned away, silent, separating plastics from recycling.

I waited.

“Yes, that’s fine,” she said.

No other words, and no mention of specifics. What exactly she was consenting to was unclear, and I couldn’t bring myself to ask. Mentioning her rape, specifically, felt out of the question, as both she and my father still seemed unwilling to even talk about my sexuality. Our fights from years ago were buried just below the surface, land mines, and I could not risk resurrecting more estrangement.

A week later I was back with my parents for another brunch. Half an hour into our conversation, my father, as if turning an unexpected corner, asked me what was in my book. His question surprised me. I glanced at my mother. He asked again. Finally, I told him that it was about my years in the therapeutic cult and the medical malpractice suit against my former psychiatrist.

“I hope you’re not dragging our good name through the dirt,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“Our good name, our good name: I hope you’re not dragging your mother’s and my good name through the filth of your homosexuality.”

Never, in all the time since coming out to them nearly twenty years earlier, had my father so directly condemned my homosexuality. I felt whiplashed by his words.

“Your ‘good name,’” I said, “is also my ‘good name.’ Besides, my book is about me, not you: You don’t have to worry about a thing.”

“Just think about what I’m saying.”

“I don’t know what you’re saying.”

“Your homosexuality,” he said, “you have to know how I feel about your homosexuality: it’s filthy, immoral, I don’t agree with it, I’ve never agreed with it, and I never will agree with it. I don’t want to be blamed for how you turned out.”

“I’ve never blamed you.”

I ended the conversation when I told both my parents that I was through, as a middle–aged man, defending who I was. I left their house in a storm.

The next day my mother called and said that I would lose the family if I proceeded with my book.

“I’ve also changed my mind,” she said.

“About?”

“I do not want any part of your homosexual lifestyle associated with my life in a book that you may write now or at any time in the future.”

Hours later my eldest brother, Frank, a stockbroker cum businessman by trade, cold and detached, contacted me by email and threatened to sue me, “on behalf of the family,” if I continued with the book. “Do not bring shame to this family,” he wrote.

My sister, Kriska, called me the next day.

“What’s going on with you?” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“Everyone in this family is really upset with you about your writing.”

“Thanks for the vote of confidence.”

“You know, Peter, none of us think that anything will ever come of your writing. You should just give it up now.”

I said little in response, made some excuse, and hung up.

As I struggled through my brother’s threat—through the self-delusion that I had build up in my mind to protect me from the truth that my own family did not have my best interests at heart, and that fear of the truth-teller can make even, or even especially, the one’s we love turn against us—I submerged myself deeper in the writing. Moreover, I cut off the limb of hope that my family might ever support me in my efforts to “tell the truth” of what had happened in the “therapy.”

Slowly, over the next several years, I continued revising the manuscript while submitting it to a (seemingly) never-ending list of literary agents and independent publishers. As the rejections—and silences—began piling up, I also became so fed up with the context of my entire manuscript—my six years in the “therapy”; everything to do with the doctor; psychiatry’s history on the subject of homosexuality; even the idea of writing about any of it—that I felt determined never to talk about it with anyone, or even to write about it, ever again. Between my need to speak the truth through my writing, and my need not to cause harm to my parents, both of whom I knew would say they’d been “harmed” should they ever read what I wrote, I felt trapped, existentially landlocked.

And yet, still, I raged on, somehow, driven by my need to understand myself better so that the writing would be better, and clearer, more thoughtful, and meaningful. Eventually, the evolving manuscript and ongoing submissions to agents and publishers became more about not giving up on a goal, and giving in to silence, than it did about getting published, an ultimate outcome over which I really did have no full control. I was a dog with a bone and would not let go. I would not give up.

I could also see that my history of trauma would never be easily nailed down into cold hard facts, a cohesive chronology of events. There was no Singular Reason why I had ended up in “conversion therapy,” let alone why I’d been sexually abused as a child. Not everything I remembered, as well, “fit” into a convenient story of who I wanted to think I was. My self-identity in the present was constantly called into question as a direct result of writing about a painful, sometimes humiliating, past, my own heart of darkness. Experts, I’d read during my ongoing research, had noted that memory tended to change over the course of a life, and that traumatic memories in particular lacked coherence, so that people and key life events remained unlinked or frozen in time, separated from a whole. As I became more willing to face the truth of my actions, and more forgiving of others’, admit to my own sense of shame, even resist my guilt and fear at writing about my parents, the writing became more nuanced, and complicated. It was not that the facts of the story of the “therapy” or my life ever changed; it was simply that, as a result of writing my life, I changed. I remembered the therapy and my childhood more forgivingly; and as a result, went back and rewrote much of the book quite differently.

The need to tell a story, especially to write it all down in a book, often isn’t rational, and definitely won’t always be validated by others. A few years after the therapy ended, in the late 1990’s, and countless times since then, more than a few people—including a couple of boyfriends—told me to “Move on with your life,” to “Let go of the past,” to “Get over it,” all comments which never quite made sense to me at the time and that I came to understand as: “I’m tired of listening to you talk about this subject.” Or maybe even: “What you’re talking about makes me uncomfortable, so will you please just stop?” I was moving on with my life when I sued the doctor—suing the doctor actually helped me to move on with my life—and when I went back into counseling soon after with a lesbian Jungian because of my, as she then described it, “shadow issues”; applied for and received my Hungarian citizenship; returned to Europe several times over where I found a home that’s closer to my bone in Budapest, birthplace to my own father; fell in and out of love with a few different men; but through it all persevered with my goal of finishing my book and seeing it through to trade publication. The paradox of it all is that I could not have continued with the memoir had I not “moved on” with my life. Otherwise, the grief of it all would have killed me long ago.

The world around moved on as well. Every leading psychological and psychiatric organization now denounced “conversion therapy.” On May 17, 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a Position Statement on the subject: “‘Therapies to change sexual orientation lack medical justification and threaten health.” Noting the long-term effects of such therapies as “feelings of guilt and shame, depression, anxiety, and even suicide,” the WHO added that practitioners of these therapies should be “subject to sanctions and penalties under national legislation. These supposed conversion therapies constitute a violation of the ethical principles of health care and violate human rights that are protected by international and regional agreements.” Ten U.S. jurisdictions, over 25 cities and counties, and even two Canadian provinces, all had passed laws or regulations banning “conversion therapy” for youth. During his term in office, President Obama condemned the practice. Efforts were now underway to classify “conversion therapy” as a fraudulent practice and illegal under the U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

As progressive as all this news seemed to be, however, experience had taught me that changing laws or “official positions” was not the same as changing hearts. At the time that I met my psychiatrist in 1989, homosexuality had long since been declassified as a mental illness and removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1973, and still he’d tried, on his own initiative, to “cure” me of my homosexuality. His own heart, I suppose, had not caught up to the then DSM-III-R.

Reconciling oneself to the lifelong effects of trauma within a culture that places timelines on how long one “should” take to grieve or mourn past harm can be onerous. “Hide your broken arm inside your sleeve,” poet Anne Sexton once wrote. More recently, in 2014, author Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D., noted in his book The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body In the Healing of Trauma, “‘Traumatic experiences are often lost in time and concealed by shame, secrecy, and social taboo.’” I suppose I decided long ago that the price I would pay for concealing my own shame—for allowing the passage of time to erase what happened between the doctor and me—would be far greater than any price I might pay for persevering with a book about events from nearly three decades ago. Most of the time I forget how long it’s been since I met the doctor—I’m just me, in the moment, living my life, trying my best to speak out against acts of incommensurable wrongdoing. Then something or someone reminds that it’s been nearly thirty years since I walked into this doctor’s office a depressed twenty-four year-old gay kid, rejected by his family and unable to reconcile his history of sexual abuse with his homosexuality, and a wave of embarrassment washes over me: Why, after all these years, are you still talking about this subject? Why can’t you let it go already? Or as a reader of one of my published articles once commented: “Gays rights are so passé.”

At a time in history when a change of government and a strike of the pen could rescind even the most basic human rights, I remind myself that the world still needs true-life stories, road maps, from those who’ve gone before us. Despite all of our post modern day liberation and flag waving, I have no doubt that at this very moment someone “out there” is still struggling with their sexuality—and how could they not? To be gay or transgender—to be anything other than a cisgender heterosexual—is to be outside the norm, and that can mean to be constantly on guard, vulnerable to ridicule, isolation, depression, thoughts of suicide. Popular media sometimes still confuses or conflates the effects of childhood sexual abuse or sexual addiction with homosexuality—with “being gay.” Even the term “conversion therapy” I now consider more like linguistic subterfuge. It is a hate crime against the individual, and of no therapeutic value, to try and “convert” or “repair” not the cultural intolerance, prejudice or hatred that caused the individual to want to “change” in the first place—basically try and become who they’re not—but a part of the individual that was never broken to begin with. I know, because I did it to myself. If my psychiatrist was a monster, then there had to have been monstrous demons inside of me, just waiting to get out.

Changing laws is not the same as changing hearts. Long after we “move on” with our life, the story of the past lives on, needing to be told. Our need to talk and to share our lives and secrets can never be silenced. Letting go of the past is not the same as not forgetting it, and speaking out in order to prevent similar types of abuse from recurring in the future. “Trauma is about trying to forget,” Van Der Kolk also wrote in The Body Keeps the Score, and so I suppose it was important for me to remember as a means of healing from my own trauma. Shame, writing my own story has helped me to understand, is written into a person early on; it is not innate. And so at some point, by whatever means, shame must, therefore, be “written out,” transmuted in some way. Writing memoir—writing my memoir, The Inheritance of Shame—helped me heal not only because the words I wrote were truth, but because I wrote.

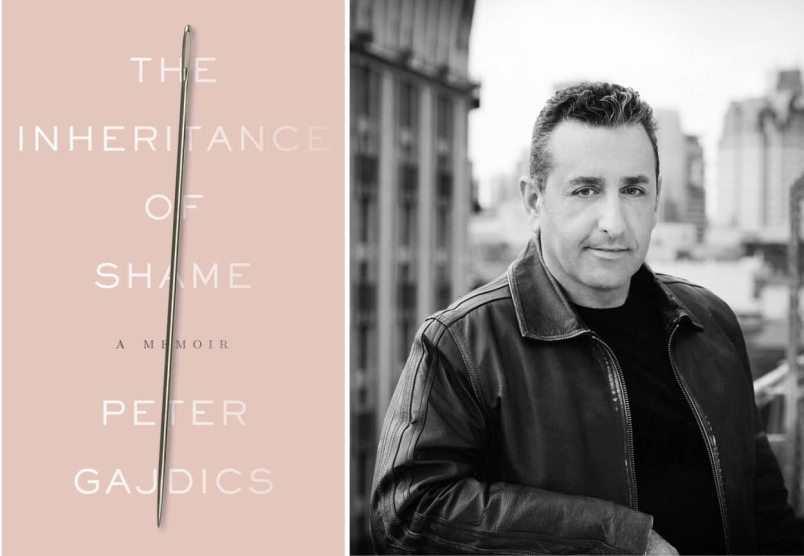

PETER GAJDICS (pronounced “Guy-ditch”) was born and raised in Vancouver, Canada, to immigrant parents from Europe. Gajdics knew from an early age that he was gay, but, for myriad reasons, that truth only seemed to cause him pain. In his early 20s, while struggling with an overwhelming sense of shame, Gajdics turned to a local psychiatrist for help. Within months he found himself embroiled in a bizarre sort of conversion therapy that attempted to “cure” him of his homosexuality. The Inheritance of Shame documents Gajdics’ six-year journey through, and eventually out of, this therapy; the legal battle with his former psychiatrist; his complicated family history; and his attempts to reclaim his life—and, most especially, his truth.

Peter is an award-winning writer whose essays, short memoir and poetry have appeared in, among others, The Advocate, New York Tyrant, The Gay and Lesbian Review / Worldwide, Cosmonauts Avenue, and Opium. He is a recipient of writers grants from Canada Council for the Arts (for non-fiction and fiction), a fellowship from The Summer Literary Seminars, and an alumni of Lambda Literary Foundation’s “Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBT Voices.” The Inheritance of Shame: A Memoir is his first book.

Visit his website.