By MJ Joseph

Undertaking a job of work in historical fiction provides this author with a happy remove from the social media-inspired addle, Martin Amis’ “fear soup” and some bored scholar’s panting for something new narratological theorems, among other things. This historical fiction writer is relaxed into a lost world’s cool, fresh cot, comforted by the wonder of how it all could have happened and the vague scent of decay vaping from old musty words that suffuse a survey of his endeavors, such as Bildungsroman, Entwicklungsroman, and Künstlerroman. This historical fiction writer lazes phenomenologically around the past, heedless of any compunction to verify a particular fact, or to casually memorialize an event, and uses the supposition of facts to proclaim his story and deport his narrative.

Thomas Pynchon’s wonderful Gravity’s Rainbow’s post-modern preposterousness certainly qualifies, here, also, but I’m afraid that sometimes Pynchon, the storyteller, resides with too many facts, stalling his tale and disorienting his poor reader’s imagination working within the channels of the narrative shaking-out before his consciousness. I can imagine that the reader, finding his attention banging into to fact after fact, historical character after historical character, around each of which his attention is asked to circle and circle, the author risks pulling the reader’s attention from the story, all together, forcing the more energetic reader to abandon the tale diminishing before him.

The You Are There, or the Having a Man in The Room, school of popular fiction, typified in the entertaining works of Herman Wouk and Ken Follett, among others, have occasionally run this risk. Follett even strains the fact-mongering to the point that he admits to employing a historical consultant for the massive, and very enjoyable, Century Trilogy and states, at the end of the first book, Fall of Giants, that, when addressing the question of “drawing the line between history and fiction…My rule is: either the scene did happen, or it might have; either these words were used, or they might have been.” What is the patient reader to do here but grab for his encyclopedia or, more likely, his iPad, in an attempt to pull his attention back into the narrative, believing that investigating the facts, or the parade of historical characters, will reveal, and please forgive the academic tone, an echoic contextuality or, perhaps, guidance going forward?

The casual reader, which I assume these authors have relied upon greatly for book sales, might just confuse truth-telling with verisimilitude and story-telling and dawdle along until his attention is caught by a sneaky peripeteia where a bodice is ripped or someone parts company with his head. But, I, the Ever Hopeful, sense that these works might really augur a new approach to reading, where the reader is asked to participate and not rely upon what he already brings to the book. The fact that he might feel compelled to research the historical facts and the facts of the historical characters being presented, might nurture a satisfying “buy-in,” as the reader holds the book in one hand and an iPad in the other.

Less popular, but intellectually more compelling historical fiction authors like, Robert Graves, Thomas Mann, Milton Steinberg and, to a lesser extent, William Faulkner, also fill their novels with historical facts and historical characters, if one assumes that Classical, Talmudic, Biblical and American Civil War scholarship is accurate and that the Roman Emperor Claudius of Graves’ I, Claudius and the Byzantine General Belisarius of Count Belisarius, Joseph and his brothers of Mann’s quartet, Joseph and His Brothers, the apostate Rabbi Elisha of Steinberg’s As A Driven Leaf and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest of Faulkner’s The Unvanquished existed. Joseph and Elisha may be a stretch and could occupy another category of fiction, but, frankly, I don’t care how they Google-out. These authors do set their readers against facts, but they completely escape my grousing by not only entertaining, but, more importantly, providing densely-layered narratives of intellectual, cultural, philosophical, and spiritual power that facilitate great human understanding and help to burn-off Mr. Amis’ “fear soup.” So, you’ve never heard of “fear soup”? Well, fetch the iPad, for crying out loud!

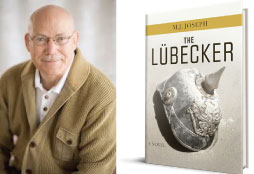

Born and raised in Florida, M.J. Joseph maintains membership in the English Goethe Society, the Siegfried Sassoon Society and other literary associations. He is a supporter-member of the Society for the Study of Southern Literature, as well as an Associate of Lincoln Cathedral. Prior to retiring, Joseph enjoyed a lengthy and rewarding career with an industrial firm where he served as CEO and managed the company’s merger with a larger international corporation. He divides his time between Europe and his home on Florida’s northern coast. M.J. Joseph and his wife Ann have two children and reside in Florida.

He is the author of The Lübecker (The Peppertree Press (September 29, 2017).