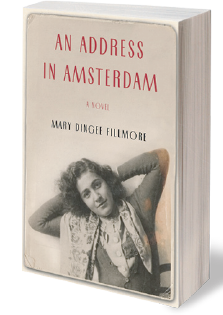

By Mary Dingee Fillmore

When the fifth course of antibiotics failed, I began to wonder. In the mirror, my cheekbones looked much too much like a supermodel’s, and my ribs were showing. I threw up anything I tried to eat. The normally cheerful nurses who had cared for me in the weeks since my accident avoided my eyes when I asked their opinion. As I grew thinner and weaker, my hospital-acquired urinary infection roared back again and again. When I wondered if I might die, my first anguish was for my partner, who had stood beside me like a great tree through this worst crisis and many others. It was spring of 2010, and we were supposed to celebrate our 25th anniversary in December. What if I was gone?

My next thought was about the novel I’d begun eight years before, and the characters in it. They couldn’t live without me, and they deserved to tell their stories about the Holocaust and resistance in the Netherlands. Why hadn’t I made more time for them? I had dozens of pages of scattered scenes, but I’d never pulled it together. No one else could. Without me, my characters would perish. Just like the murdered people who inspired the novel: almost three-quarters of the Jewish people in the Netherlands, countless non-Jewish resistance workers, and others. I had been writing to bring them back to life, to remind us today that we still face the choice to collude, collaborate or resist. And that resistance is always possible, and honorable, whether or not it is effective.

As the nurses pierced my emaciated body with shot after shot of antibiotics, I thought of my fictional heroine, Rachel Klein, an 18-year-old who is falling in love as the Nazis invade her country. How did she find the courage to join the underground and deliver papers under the noses of the Nazis? Photographs of some Jewish people from that time show them smiling and laughing even while wearing the star. How did they sustain their joy in life? What kept people like Rachel choosing to do the right thing?

I’d always thought I’d have time to explore these questions and finish the book after I got older and cut back on my consulting work. Someday. Now, as I sat in the wheelchair and looked at my gaunt face in the mirror, I realized it might never happen. And I vowed that, if I lived, I would finish writing Rachel’s story, whatever it took. Her world had obsessed me since my first long stay in Amsterdam in 2001, when I first went to the Dutch Resistance Museum and learned about the dilemmas people faced in 1940-45. While continuing my business consulting to nonprofits, I had returned to Amsterdam and kept on doing research, as well as earning an M.F.A.Even so, my progress on the novel came only in bursts until my accident.

The eleventh course of antibiotics worked, and I finally went home in June 2010. For the next two years, I struggled with the dire aftereffects of the drugs, which had both saved my life and destroyed my digestive tract. I was sick with the equivalent of a bad intestinal flu for the better part of two years. In my early months at home, I often could only manage 15 minutes a day of fact checking for the novel. If Rachel and her friend were walking in the park, was I sure they hadn’t been banned from public places yet? What were they talking about? Had that happened while the parks were still open? Questions at that level I could handle even if I didn’t have the energy or mentality to write. At other times, I could tinker with a sentence or a paragraph. The most rewarding days were when I was fully back in 1940s Amsterdam, seeing the canals clearly with the Nazi posters pasted on pillars, writing about the characters and seeing their stories unfold.

As my health slowly returned, I stitched together the bits and pieces of the novel much like a quilter. I looked for juxtapositions and sequences; I discarded what didn’t fit or add to the story. I immersed myself back in Amsterdam’s museums and archives, as well as continuing my research in the U.S. At the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, I held a leathery mustard-yellow star stamped “Jood” in my hands. Piles of books and photographs at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington sharpened my picture of Amsterdam under the Nazis.

My writing group stuck with me through the whole process. Members wheeled me to meetings when the distance from the door to the meeting room was too far for me to walk with my broken knee. They critiqued and suggested and supported, as did numerous friends. My longtime teacher, Deena Metzger, helped me come to terms with how my life had changed utterly in a few seconds – and how I could use what I’d learned in my book. For the first time, I understood what it is to be trapped and totally dependent on other people, as my characters were when they hid.

Most writers say they get tired of revising their books. I never did. Right after I came home in 2010, half an hour of working on An Address in Amsterdam gave me purpose and meaning at a time when I could do almost nothing else. I was grateful to be able to revise even one sentence well. When I could do more, I rejoiced in seeing the rewritten pages accumulate. In 2014, my twelfth year of working on the book, I had the joys of a professional editor’s help and six blissful months in Amsterdam to do a final rewrite. The decision to apply to the hybrid She Writes Press has served me well, giving me not only a respected publisher but also a circle of other women authors to learn from and support.

Now that I have my full strength again, I want to bring Rachel’s story into the light. She reminds us of the courage that precedes us, and challenges us to do a fraction as well as in our own times. I don’t think I’ll get tired of my book, or of Rachel.

After all, I saved her life, and she helped save mine.

MARY DINGEE FILLMORE fell in love with Amsterdam in 2001 and has been returning there and researching its complex history ever since. A longtime professional facilitator for nonprofits and government, she gives talks for the Vermont Humanities Council titled “Anne Frank’s Neighbors: What Did They Do?” and writes at maryfillmore.com and seehiddenamsterdam.com.