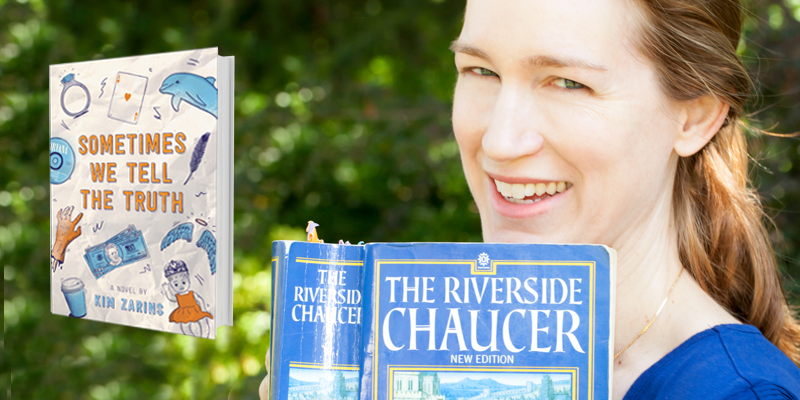

Kim Zarins has a PhD in English from Cornell University and teaches medieval literature at Sacramento State University. Her YA contemporary retelling of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, Sometimes We Tell the Truth, will be released on September 6, 2016. When she isn’t reading, writing, or teaching, she hangs out with her family in Davis, CA, and coaxes a scrub jay named Joe to take peanuts from her hand. You can find her at www.kimzarins.com, on Twitter @KimZarins, and on her public page on Facebook at Kim Zarins.

Faith Aeriel spoke with Zarins about Sometimes We Tell the Truth.

Q. Why did you want to write a story that was a reimagining of The Canterbury Tales?

A. As a medievalist, I love the idea of bringing Chaucer’s masterpiece to modern readers with no prior knowledge of Chaucer needed. The Canterbury Tales is a funny, thoughtful, and surprising story about telling stories. It really lends itself to a contemporary setting and was pretty much the ideal project for me, blending my passion for both young adult and medieval literature.

Q. Why did you decide to use children as your characters instead of adults that may have been more traditionally in line with Chaucer’s original?

A. I used teenagers partly because it’s a young adult novel, but Chaucer’s over-the-top characters often seem like teenagers in spirit. For example, in the original, the Wife of Bath is a woman in her forties, but her humor, red stockings, and rebelliousness convey a teenage personality. It was fun changing the characters into teens—and also fun switching genders to allow more women to join the road trip. Why did you choose to tell the story from Jeff’s perspective? In the original, Chaucer writes himself into the story as the narrator. I kept that aspect, and Jeff Chaucer becomes the narrator and a wallflower main character torn between peer pressure and his feelings. Since Jeff is a writer, he thinks deeply about the stories and is the most transformed by them. His character growth gives the story an overall story arc, but other characters also process and respond to the stories, and they change in their own ways. The book isn’t a short story collection but a novel in which stories become part of the characters’ journey, and Jeff seemed to offer the best vantage point to convey the power of stories.

Q. Why did you make the rule that the students’ stories should be fictional?

A. This isn’t specified as such in the original, but I did this because Chaucer’s characters tell fictional pieces with only a few personal anecdotes. Also, I didn’t want a tale to win the storytelling competition because of its raw personal connection to the teller—having the teens tell memoir would complicate judging the stories for their literary merits. Of course, there are still lots of personal narratives hiding beneath the surface, and part of the point of the novel is that stories reveal things about people and can come from deep places.

Q. Were you inspired by any other retellings of The Canterbury Tales, such as One Amazing Thing by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni?

A. One Amazing Thing is definitely on my to-read list—from what I’ve heard, it seems more like a retelling of medieval author Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, in which a disaster (plague) is the catalyst for storytelling rather than a road trip, which is the catalyst in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Mostly to stay inspired, I reread Chaucer, Chaucer scholarship, and young adult novels.

Q. How is retelling a story different than writing your own original story? Did you feel like you had creative license over the characters and events or did you feel somewhat limited by the precedent set by Chaucer?

A. That’s an interesting question, because if Chaucer was writing today, we’d ask it of him—did he feel unoriginal retelling tales by classical and medieval authors such as Ovid and Boccaccio? Medieval authors loved retellings and never saw them as unoriginal for their shared elements, and I’m influenced by that perspective. I loved retelling Chaucer and his retellings of other authors. I never felt limited by retelling tales—quite the opposite. It was part of the fun. Retellings speak to two audiences, the ones new to the material and the ones who can hear the echo of past works. It’s complex and rewarding to write in layers.

Q. How did teaching Chaucer and teaching writing for young audiences influence Sometimes We Tell the Truth?

A. In writing this book I drew more from my teaching experience as a medievalist than as a teacher of creative writing. Chaucer is a demanding author for college students in that he writes in a different language, Middle English, which is harder than Shakespeare’s Early Modern English, but easier than the Old English of England’s earliest poems like Beowulf. Despite the effort involved, reading Chaucer is rewarding because of the wonderful characters and tales. Chaucer makes my students laugh out loud! I wanted to bring out that humor to entertain readers but also make them think. In my Chaucer classes, I often make comparisons to modern literature and culture to show how relevant and thought-provoking Chaucer is, and it was fun to work some of class discussion and that approach into the novel.

Q. How did your writing process with this book differ from the books you have written previously (The Helpful Puppy, Playful Bunny)?

A. They differ tremendously. Those were short picture book texts for very young children with simple themes of friendship and belonging. Of course, those themes continue in all literature and life, but in this novel, questions of identity, community, and relationships are allowed to be more complex.

Q. Do you think there’s anything taboo that shouldn’t be written about in YA books? Why or why not?

A. Young adult books have a vast range of subject matter because there is a vast range of readers. Some teen readers are not ready for the mature themes of edgy YA novels—which is fine—but other more experienced teens are ready for those themes and deserve to see those themes in books. In addition, a book is a safe place for a reader to explore certain issues that they may or may not have experienced in real life. Reading such books may help give these teens the language to process what is going on in their own lives and as well as explore various topics from a safe distance.

Q. What do you hope readers come away with when they finish Sometimes We Tell the Truth?

A. In my novel, I don’t tell readers they are reading a Chaucer retelling until they get to the Afterword at the end. I’d love for these readers to give Chaucer a chance in high school and college.

Regardless, I hope they come away with the understanding that each of us has our own story to tell, and we’re all worth listening to—we’re all more than the sum of our parts.

Faith Aeriel is a freelance writer and journalist. She has formerly worked as Associate Editor for Manhattan Book Review, San Francisco Book Review, and Kids’ BookBuzz, during which time she was responsible for writing articles, blog posts, and interviewing authors, as well as editing and managing incoming content for the websites. Faith loves books, cinnamon rolls, and cats.

Faith Aeriel is a freelance writer and journalist. She has formerly worked as Associate Editor for Manhattan Book Review, San Francisco Book Review, and Kids’ BookBuzz, during which time she was responsible for writing articles, blog posts, and interviewing authors, as well as editing and managing incoming content for the websites. Faith loves books, cinnamon rolls, and cats.